|

The Cattle Drive and Westward Expansion uses the College, Career, and Civic Life (C3) Framework's Inquiry Arc as a blueprint to lead students through an investigation of cattle drives during the 1880s. The Inquiry Arc consists of four dimensions of informed inquiry in social studies:

- Developing questions and planning inquiries;

- Applying disciplinary concepts and tools;

- Evaluating sources and using evidence;

- Communicating conclusions and taking informed action.

The four dimensions of the C3 Framework center on the use of questions to spark curiosity, guide instruction, deepen investigations, acquire rigorous content, and apply knowledge and ideas in real world settings to become active and engaged citizens in the 21st century.1 For more information about the C3 Framework, visit socialstudies.org.

C3 Table- Cattle Drive and Westward Expansion |

Historical Context of the Cattle Drive

Cattle are not native to the United States. They were introduced by early explorers and settlers from Spain and England. Some cattle were introduced directly to the United States, but others came indirectly by way of Mexico. In 1690, the first herd of 200 longhorns were driven North from Mexico to a mission along the Sabine River, an area which is now part of Texas. Texas became independent in 1836 and the Mexicans moved South, leaving their cattle behind. Texas farmers began raising the Mexican cattle for their hides and tallow. Tallow was made from rendered animal fat and was used to make candles, soap, and other products. Although beef was consumed in the 1800s, the lack of refrigeration and preservation methods limited its consumption. Today, cattle are primarily raised for their beef.

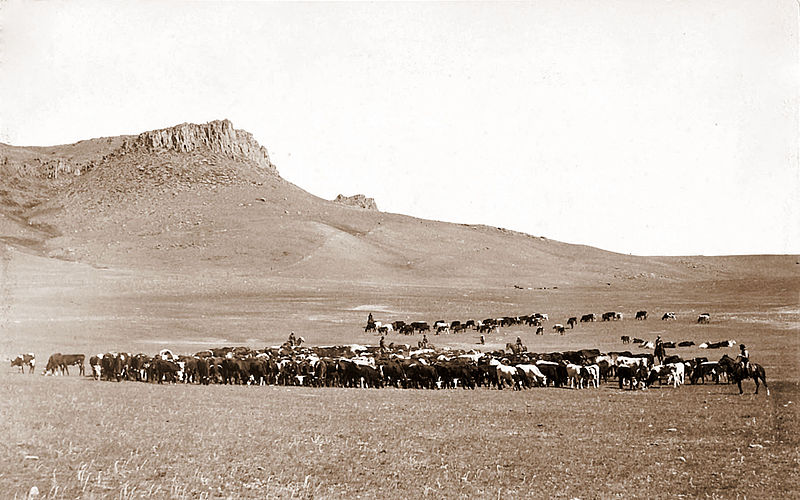

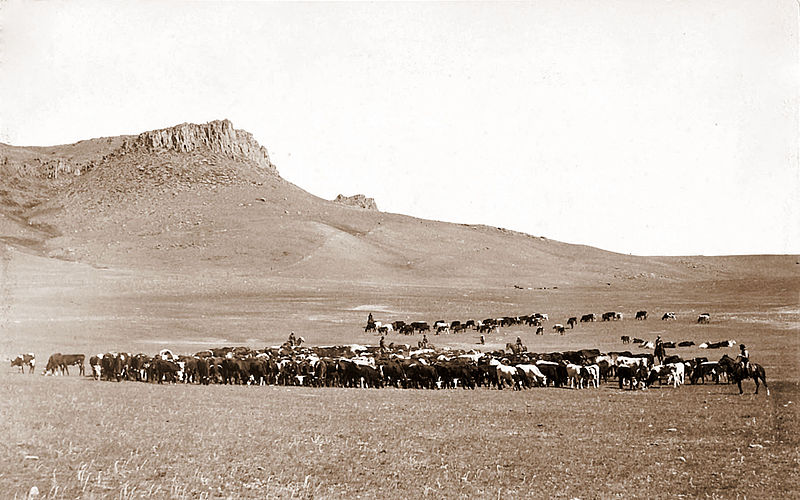

Cattle roundup near Great Falls Montana, circa 1890. Source: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Cowboy

The first cattle drives headed West from Texas to San Francisco to the area where gold miners could be found (1849). Cattle ranchers could sell their cattle for 5-20 times the amount they could in Texas. The cattle market in California dropped along with gold mining. When the Civil War erupted (1861), many cattle herds were left behind on the open range. Cattle ranching halted for a time; however, the longhorn population grew as they continued to graze and reproduce on the prairie. After the war (1865), large cattle herds and consumer demand in cities resulted in cattle drives to locations where the railroad had a railhead. These towns were called "cow towns." When the animals arrived they would be sold and sorted for distribution to cities for slaughter and market.

Cattle Drive Map. Source: National Agriculture in the Classroom

Cattle drives continued for about 20 years (through the late 1880s) until the railroads grew and ranchers had closer access to railheads. Rail transport not only changed the speed of delivery, but as tracks were laid and refrigerated rail cars were developed, trains could go to where the cattle were located. This reduced rangeland degradation on the way to market and kept weight on the animals leading up to harvest because they no longer needed to walk 500-1000 miles to reach the market.

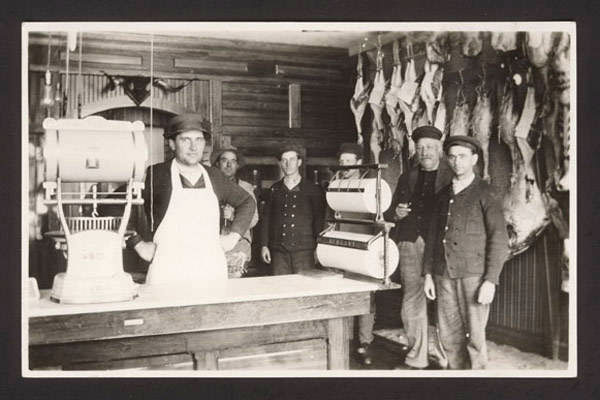

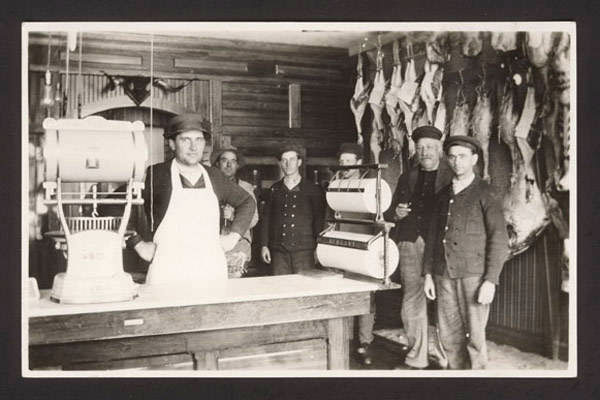

Butcher shop, circa 1890. Nebraska State Historical Society. Source: http://www.nebraskahistory.org/publish/publicat/timeline/labor_day_1890.htm

Life on the Trail:

A typical cattle drive pooled together cattle from several ranches. Most drives consisted of a total of 1000-3000 head of cattle. The historical era of the cattle drives took place before the wide-spread use of fencing. Cattle roamed free and owners used brands and earmarks to identify the cattle they owned. Cattle brands were registered and could only be used by the owner. When a cattle drive was organized, the trail boss kept record of the brands and earmarks in the trail herd. After accounting for each ranches herd, the cattle were branded for identification with a single trail brand for the drive.

A 12-person crew could manage most cattle drives. While most of the crews were composed of men, there were some women who drove cattle to the railhead. As discussed in the book "Texas Women on the Cattle Trails" by Sara R. Massey, like men "some [women] took to the trails by choice; others, out of necessity. Some went along to look at the stars; others, to work the cattle. Some made money and built ranching empires, but others went broke and lived hard, even desperate lives." Men, and some women, then had their own responsibilities and typically held positions that included the following:

- Trail Boss: The trail boss was the leader of the cattle drive. He was in charge of all the men and equipment. An average trail boss would have earned around $125 per month. The trail boss rode at the head of the herd. He collected the money when the cattle were sold and was responsible for paying the crew.

- Cook: The cook was the second most important position on the cattle drive. He traveled about a mile ahead of the cattle and crew. He rode on the "chuckwagon" which carried the food, water, and provisions for the crew. The cook prepared each meal, found campsites nightly, and filled in for other odd jobs as needed. Cooks earned about $60 per month.

- Cowboy: Cowboys worked the cattle and were paid $20-$40 per month. The most experienced cowboy was known as the "Segundo" and rode evenly with the trail boss. On each side of the herd were the "Swings" followed by the "Flanks" and finally the "Drag" riders. The drag riders had the worst position as they were behind the herd. Not only were they stuck riding in the dust, but they were responsible for pushing the lazy and slow cattle to keep them with the herd.

- Wrangler: The Wrangler was usually the youngest in the crew. His job was to care for the horses. Each cowboy on the drive had three or four horses. The wrangler fed, saddled, and cared for the entire herd of horses and was responsible to drive the horses that weren't being ridden.

There were numerous trails used. Noted trails include the Chisolm Trail, which led from Texas to Kansas. It was named for the Indian trader Jesse Chisholm. The original trail expanded as time passed due to cattle herds making new trails. The Chisholm Trail became obsolete in the mid-1870s after an interstate railroad came to Texas. The Goodnight-Loving Trail crossed West Texas. It was established by Charles Goodnight and later Oliver Loving. The route was longer, but generally safer.

There were many dangers on the trail. Indian attacks were a threat in some areas along a cattle drive. Flooded rivers caused delays and drought often made it difficult to keep the cattle watered. Stampedes were a real danger. The herd could be spooked by a variety of sights, smells, and noises, but lightning was the most common. To stop a stampede the cowboys would run on horseback to the head of the herd and turn them to the right, directing the stampede into a circle. In time the cowboys made the circle smaller and smaller allowing the cattle time to calm down and stop running.

Life on the trail was long and lonely. Most drives lasted 3-5 months depending on the distance they needed to travel and delays they experienced along the way. A typical drive could cover 15-25 miles per day. Although it was important to arrive at their destination on time, the cattle needed time to rest and graze. Otherwise they would be very thin when they arrived at the markets, which decreased their value.

The End of Cattle Drives:

The historical era of the cattle drive lasted about 20 years. It began shortly after the Civil War and ended once the railroads reached Texas. This transportation system provided a route for beef to travel safely from the farms and ranches where it was produced to the markets where it was sold. This 20 year stretch of time left imprints on western culture and hobbies that have lived on. Chaps, cowboy hats, boots, old western songs, rodeos, and of course the cowboy all have roots stretching to this era in history.